For whatever reason, anything remotely useful in health & fitness eventually gets coopted and turned into madness. Zone 2 training is no different. It has become popularized, misunderstood, and over-complicated, all the while receiving nonsensical criticisms, mostly for things it isn't.

So, in the spirit of progress, and in an attempt to dispel some of the nonsense, here are a few of the many, many myths, and our responses. Part 3 of this series will dig more deeply into the science, which we allude to here, and Part 4 will go into more detail on tips and techniques.

The Myths

This list is by no means exhaustive, but it is a start. If you come across others, let us know, and we will add them to the list.

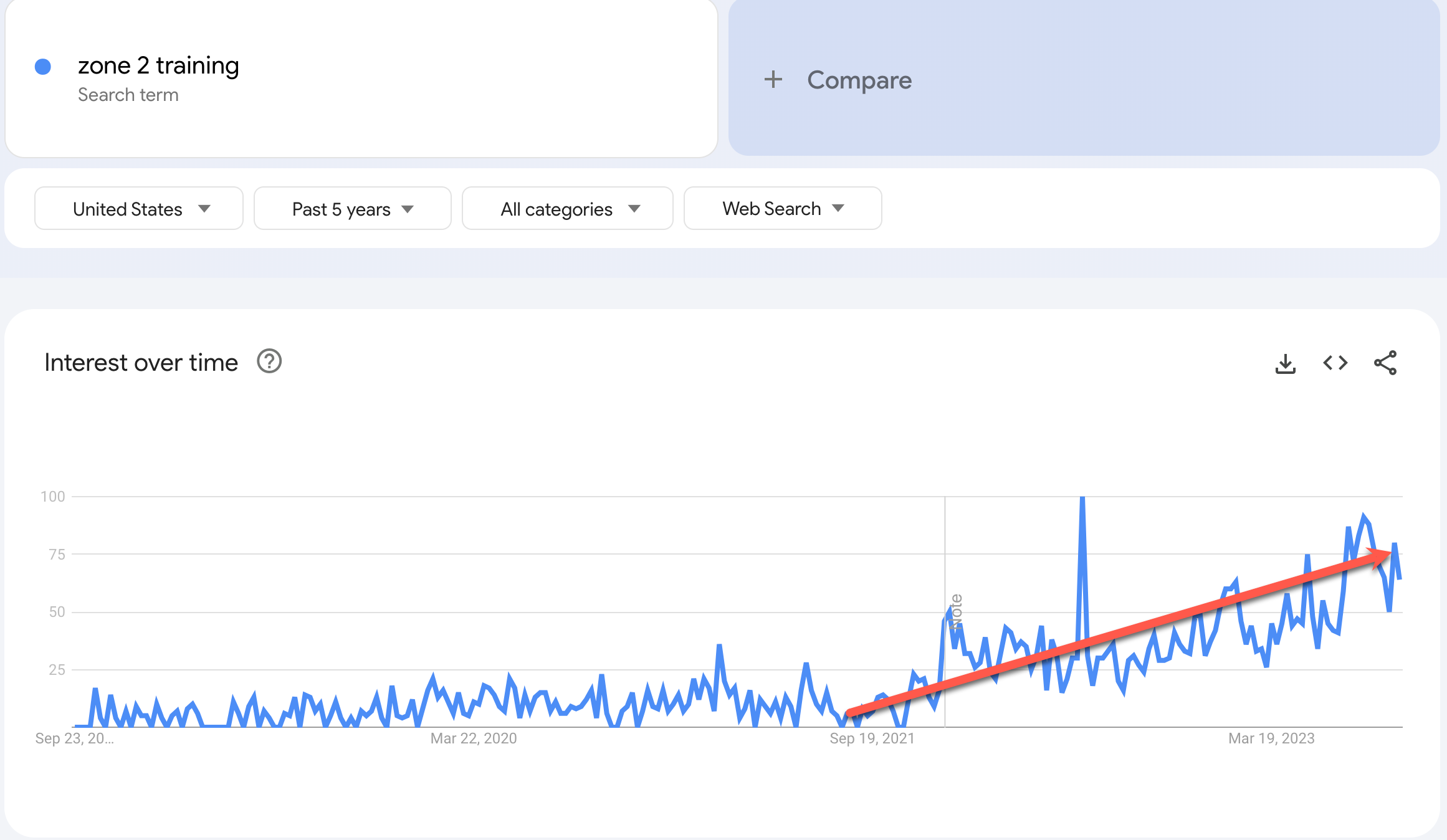

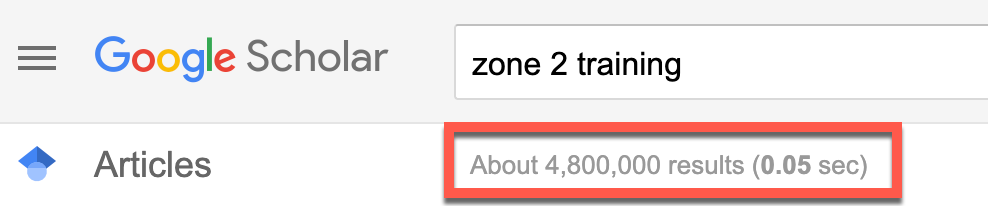

Zone 2 training is a fad

While Zone 2 training is increasingly popular, and there is a lot of misguided information out there, it isn't a fad, if by that you mean something fashionable without evidence or effectiveness to justify its use. That is simply untrue. Hang out on Google Scholar for a bit and go wild reading the decades of work. Geek out, bro. There are hundreds and hundreds of papers, which generally demonstrate that recreational athletes improve with low-intensity training. Of course, the average person's fitness would improve by doing almost anything, given that they don't get much/any exercise.

HIIT (or Maffetone (or whatever else) is better

We can't say this enough. What is better is what you continue to do regularly and without injury or detraining. HIIT can be effective, but most people won't stick to it, and, for reasons we will get into an upcoming post in this series, HIIT's effectiveness varies depending on your goals. The physiological effects of HIIT vs. low heart-rate training vary, as do their respective effects on mitochondrial volume and efficiency. Sure, there is a role for HIIT training, just far less than you think.

At the other end of the spectrum, Phil Maffetone has some straightforward ideas about low-intensity training—target a heart rate of 180 minus your age—which may work for you. The Maffetone method does get a bit complicated with higher ages, and he has fudge factors for that, but many find it easier to think in terms of zones. For many of us, our Maffetone-determined heart rate is significantly lower than our first lactate threshold (top of Zone 2), as determined by other methods. While this guarantees we are in a low HR zone, it might not be enough stimulus on some days.

You have to work hard to go hard

While it can be counterintuitive, metabolic pathways (fat oxidation, lactate clearance, mitochondrial volume, and efficiency) can be improved at low levels of intensity. Your mitochondria need stressors, and low-intensity training can provide that stress and drive efficiency and mitochondrial health. Mitochondrial volume and function require different stressors, though. That's the reason we will not tell you that hard stuff isn't needed, too, but that isn't the same thing as saying you need to suffer like a dog out there to make any fitness progress. You don't. And, in particular, with age, given the rapid loss of fitness that comes with injuries, some of which are more likely by pushing too hard, avoiding injuries should be high on your list.

If you run/bike/etc. slow, you go slow

This is a variant of the above myth, and loved by many high school cross-country coaches who think making their athletes vomit after a round of 800m intervals is the path to competitive success. While it's true that training for sprinting requires sprinting, most of us aren't training to be sprinters. Most of us—by which we mean the people reading this—are training as a structured way to build fitness and live longer, healthier lives. Granted, you may end up sprinting a little, but you would be amazed how little sprinting training you need to do. Did anyone say none?

Heart rate zones are a myth

Heart rate zones are not mathematical certainties but convenient shorthand for how our body responds to effort and channels energy given a certain load or stimulus. We target these zones because we know what is happening from a physiological perspective within each of these zones. Our watches tell us our heart rate, not our maximal fat oxidation or lactate levels. Our watches also don't tell us how much type 1 vs. type 2 muscle fiber recruitment is going on. With a solid understanding of the physiology of training, we can target these changes by knowing our heart rate. We are actually targeting physiological adaptations and changes by using heart rate as a proxy for the adaptations we are trying to generate.

There are measurable physiological changes that occur with increasing or decreasing effort intensity, and we can, as a shorthand, talk about those areas as "zones." From a physiological perspective, heart rate zones are used as a proxy for whether or not we are targeting maximal fat oxidation, our first or second lactate threshold, our lactate shuttle, mitochondrial flexibility, volume, efficiency, or our VO2 max.

Now, do the zones have sharp lines between them? No, this is more like crossing ecological zones, where things change over a short-ish distance, and steadily, you leave the rainforest and end up in the savannah. It wasn't just bing-bang. Metabolic zones are like that, too, but even so, thinking in terms of zones is helpful as we get into below and in subsequent entries in this series.

For our paid subscribers, the rest of this post, as well as the next two posts in this series, will go into far more detail about this.

Read the full article

Sign up now to read the full article and get access to all articles for paying subscribers only.